A. Antony Selvi, S.

Prakash Shoba, and P. Thenmozhil, from the different

institute of the India wrote a research article about, Medicinal

Plant Trading in Kovilpatti Taluk, South East Tamil Nadu. entitled, Trading

of medicinal plant products in Kovilpatti Taluk, Thoothukudi, South East Tamil

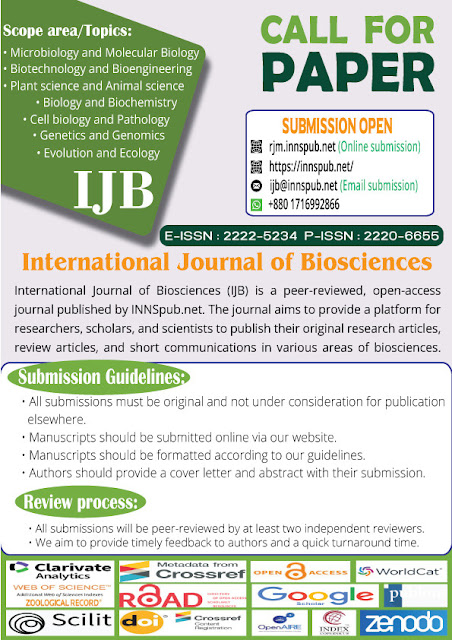

Nadu, India. This research paper published by the International Journal of Biosciences | IJB. an open

access scholarly research journal on Biology under the affiliation of the International

Network For Natural Sciences | INNSpub. an open access

multidisciplinary research journal publisher.

Abstract

Pharmaceuticals, herbal

remedies, teas, spirits, cosmetics, sweets, dietary supplements, varnishes, and

insecticides are just a few of the processed and packaged goods made from

medicinal and aromatic plants (MAPs), which are also created in large

quantities. In many instances, using basic materials from plants are

considerably less expensive than using substitute chemical substances. Around

the globe, 70,000 plant species are thought to be used in folk medicine.

Objectives: The purpose of this investigation was to: document the most traded

species of medicinal plants in the Kovilpatti Taluk, Thoothukudi District, Tamil Nadu,

including parts used, Description of medicinal plant products, sourcing

regions, harvesting frequencies; Materials and Methods: to profile and

investigate the rationales for the involvement of stakeholders in medicinal

plants related- activities; to understand socio-economic attributes of

stakeholders who were traders, collectors. to assess constraints and

opportunities for sustainable management of medicinal plants in the Thoothukudi

District. The present also highlights the available medicinal plant products

utilized for religious and rituals purpose in the herbal medicinal shop. The

present study highlights the available medicinal plant products, quantity sold

and the price of the medicinal plant products in the above retailer shops.

Results: To study the socio-economic profiles of those involved in the trade,

factors influencing prices of products and the impact of commercial harvesting

on selected species. To record the available medicinal plant products utilized

for religious and rituals purpose in the herbal medicinal shop. To find out

ways and means to preserve and conserve these plant diversity treasures.

Read more : Butterfly Diversity in Cadaclan, San Fernando La Union, Philippines | InformativeBD

Introduction

Because forests offer fresh water, oxygen, and a range of beneficial forest products for both medicine and food, people who live in lowland and mountainous locations have profited significantly from them (Kala, 2004). The values that have historically been connected to various types of forests and the products they provide, such as medicinal herbs, have taken on a substantial significance in the twenty-first century (Stein, 2004; Kala, 2004). Additionally, more natural components, such as extracts from different medicinal plants, are being included in cosmetic goods (Kit, 2003). China and India, the two largest countries in Asia, contain one of the most varied selections of certified and generally well-known medicinal plants (Raven, 1998). Since the Indian subcontinent is well known for the wide range of forest products it produces and its long-standing medical traditions, it is urgent to uphold these traditional values in national and international contexts while also realising the ongoing trends in traditional knowledge development. Developing this sector could benefit persons in low-income areas who largely depend on medicinal plants as an additional source of income by raising living standards (Myers, 1991; Lacuna-Richman, 2002).

In addition, indigenous

knowledge on the usage of lesser-known medicinal herbs is rapidly dwindling

(Kala, 2005). The realisation that traditional knowledge of many beneficial

plants for medicine had been steadily fading in the past despite fresh interest

at the moment made the necessity to examine the valuable information with the

intention of growing the medicinal plants sector clear. Traditional healers

faced an acute issue with the legal acquisition of wildlife products needed for

traditional treatment. Conservationists and traditional healers observed high

amounts of harvesting outside of protected areas (Botha, 1998).

Medicinal plants wealth

in India Of the 17,000 different higher plant species found in India, 7,500 are

utilised medicinally (Shiva, 1996). Based on the indigenous flora, this

percentage of medicinal plants is the highest percentage of plants used for

medical reasons in any country on the planet. Following Ayurveda and Siddha as

the two oldest medical systems in the Indian subcontinent, Unani and Siddha

have independently identified about 2000 different species of medicinal plants.

The production of 340 herbal medications and their conventional uses are

described in the Charka Samhita, an old literature on herbal medicine

(Prajapati, 2003). Approximately 25% of medications in the modern pharmacopoeia

are currently derived from plants, and many others are synthetic counterparts

made from prototype chemicals identified from plant species (Rao et al., 2004).

Demand for medicinal

plants Given that human societies in developing countries rely heavily on

forest products for their economy and way of life, the ongoing growth in the

human population is one of the factors raising concerns about our ability to

meet our daily needs for food and medication. According to Samal et al. (2004),

this phenomenon is causing the forest and the forest products to continuously

erode, making it difficult to satisfy demand and preserve valuable bio resources.

The Materia Medica is steadily expanding to include more and more species, but

the requirements for their purity and accurate identification are not keeping

up (Kaul, 1997). Only a small portion of the market's functioning, not on the

whole, is revealed by the rates for medicinal plants and their derivatives on

the open market.

The continued expansion

in the number of people is one of the issues causing worry about our ability to

meet our daily demands for food and medication because human cultures in emerging

countries rely significantly on forest products for the economy and way of

life. Samal et al. (2004) claim that this phenomena is causing the natural

environment and its products to steadily deteriorate, making it challenging to

meet demand and protect priceless bio resources. The number of species in the

Materia Medica is continuously increasing, but the standards for their purity

and exact determination are not keeping up (Kaul, 1997). The prices for

medicinal herbs and derivatives of them only partially, not entirely, show how

the market functions.

Collection of medicinal

plants The majority of dried herbs used in medical and aromatic plant trade

internationally. The majority of the time, both wild and developed kinds is

traded in their "crude" or "unprocessed" forms. Plant sales

are increasing on a global scale. More than 95% of the 400 plant species

utilised to create medication by various enterprises come from India's wild

populations (Udiyal et al., 2000). Due to continued use of several wild medicinal

plant species and severe habitat loss over the past 15 years, a number of

highvalue medicinal plant species have experienced population decreases over

time (Kala, 2003). The biggest threats to medicinal plants are those that have

an effect on any kind of biodiversity that is used by humans (Rao et al., 2004;

Sundriyal, 1995).

The decline of

customary laws that have regulated the use of natural resources is one reason

putting medicinal plant species in jeopardy (Chimire et al., 2005; Kala,

2005).These ancient rules have been demonstrated that they are easily

undermined by modern socioeconomic factors (Kit, 2003). Because it is believed

that wild plant kinds have higher chemical contents, manufacturers typically

prefer them over domesticated therapeutic plants. The seasons in which a

species is harvested and the various stages of a species' growth also have an

impact on the variety in chemical composition. The industry for medicinal

plants is unreliable because of the vast clandestine commerce. The financial

benefits and administrative costs for wild populations are frequently

underestimated (Kit, 2003; Kala, 2004). Research conducted locally frequently

provide vital data that support research conducted nationally or regionally.

The current study aims to quantify the trade in medicinal plant goods in Tamil

Nadu, Thoothukudi District, India, and to investigate socioeconomic factors

that may have an impact on resource management.

Reference

Anonymous. 1996. Sectoral Study an Indian Medicinal Plants-status, perspective and strategy for growth. Biotech Consortium India Ltd., New Delhi.

Bevill, Bhattarai, 1997.

He and Ning, 1997; Lange, 1998 ; 2002 ; Robbins, 1999 ; Kathe 2003.

Botha J. 1998.

Developing an understanding of problems being experienced by traditional

healers living on the western border of the Kruger Natoinal Park : foundations

for an integrated conservation and development programme. Development Southern

Africa 15, 621-634.

Chimire M, Capasso G,

Di Leo VA, De Santo NG. 1994. A history of salt. American Journal of

Nephrology 14, 426-31.

FAQ. 2003. State

of the world’s forest. Rome : Food and Agricultural Organization.

Jablonski Joshi K,

Chavan P, Warude D, Patwardhan B. 2004. Molecular marks in herbal drug

technology. Current Science. 87, 159-165.

Joshi K, Chavan P,

Warude D, Patwardhan B. 2004. Molecular marks in herbal drug technology.

Current Science 87, 159-165.

Kala 2005. Current

status of medicinal plants used by traditional vaidyas in Utaranchal state of

India. Ethnobotany Research and Application 3, 267-278.

Kala CP. 2004.

Revitalizing traditional herbal therapy by exploiting medicinal plants : Acase

study of Uttaranchal state in India in indigenous knowledgr : Transforming the

academy, proceedings of an international conference. Pennsylvania : Pennsylvania

State University. 15-21.

Kala CP. 2000.

Status and conversation of rare and endangered medicinal plants in the Indian

trans-Himalays. Biological Conversation 93, 371-379.

Kala CP. 2002.

Medicinal plants of Indian trans-Himalaya. Dehradun. Bishen Singh Mahindra Pal

Singh.

Kamboj VP. 2000.

Herbal Medicine. Current science 78(1), 35-39.

Kaul MK. 1997.

Medicinal plants of Kashmir and Ladakh. New Delhi: Indus publishing Company,

New Delhi.

Kit. 2003.

Cultivating the healthy enterprise in Bulletin 350. Royal Tropical Institute.

Amstardam, Netherland.

Nautiyal S, Roa KS,

Maikhuri RK, Negi KS. Kala CP. 2002. Status of medicinal plants on way to

Vashuki Tal in Mandakini Valley, Garhwal, Uttaranchal. J. Non-timber forest

products 9, 124-131.

Rao MR, Palada MC,

Becker BN. 2004. Medicinal and aromatic plants in Agro. Agro-Forestry

Systems 61, 107-122.

Satakopan S. 1994.

Pharmacopeial Standards for Ayurvedic, Siddha and Unani Drugs. In Proceedings

of WHO Seminar on medicinal plants and quality Control of Drug Used in ISM.

Ghaziabad. p, 43.

Sharma AB. 2004.

Global medicinal plants demand may touch s Trillian by 2050. Indian Express.

Shiva MP. 1996.

Inventory of forestry resources for sustainable management and biodiversity

conservation. Indus Publishing Company, New Delhi.

Stein R. 2004.

Alternative remedies gaining popularity the Washington post.

Sundriyal RC, Sharma E. 1995.

Cultivation of medicinal plants and orchids in Sikkim Himalaya. Almora. GB

Plant institute of Himalayan Environment and Development.

Ticktin. 2004. The

ecological implications of harvesting non-timber forest products.J.Applied

Ecology 41, 11-21.

Weekely Williams VL,

Balkwill K, Wittkowski ETF. 2000. Unravelling the commercial market for

medicinal plants and plant parts on the Witwatersrand. Economic Botany 54, 310-327.

Source : Trading of medicinal plant products in Kovilpatti Taluk, Thoothukudi, South East Tamil Nadu, India

%20in%20full.JPG)

0 comments:

Post a Comment