E. Soriano, Veronica P.

Mangune, and Melody S. Pascua, from the different institute of the Philippines.

wrote a research article about, Low-Cost Cultivation Protocol for Ganoderma

lucidum. entitled, Development of low-cost cultivation protocol for Ganoderma

lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst. This research paper published by the International journal of Microbiology and Mycology (IJMM). an open access scholarly research

journal on Microbiology. under the affiliation of the International

Network For Natural Sciences | NNSpub. an open access

multidisciplinary research journal publisher.

Abstract

Ganoderma lucidum commonly known as lingzhi mushroom, or reishi mushroom in some countries, is an edible

mushroom known for its medicinal value. This study evaluated the optimum

culture media, grain spawn and substrate formulation for the cultivation

of G. lucidum. The use of different low-cost culture media, grains and

substrate formulations in the preparation of pure cultures, grain spawn bags

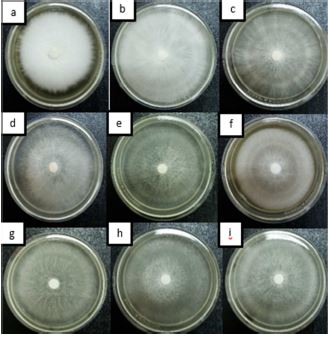

and fruiting bags of G. lucidum were tested. The largest mycelial

diameter was observed in Potato Sucrose Agar (93.45mm) which was significantly

higher among all the treatments used. It has very thick mycelial density.

Cracked corn as spawning material had the shortest incubation period of 14

days, which showed significant difference compared to sorghum seeds and barley

grains. The use of cracked corn also incurred the lowest cost and highest

return of investment in grain spawn bag production. For fruiting bag

production, substrate combination of 50% sawdust and 30% rice straw

supplemented with 20% rice bran was the best formulation for fruiting bag

production of G. lucidum which had the highest yield with a mean

value of 91.30g and biological efficiency of 20.29%.

Read more : Bidens pilosa Linn.Aqueous Extract against Postharvest Fungal Pathogens | InformativeBD

Introduction

Mushrooms are

considered ultimate healthy food and dietary supplements. They contain

proteins, carbohydrates, minerals, vitamins, saturated fatty acids, phenolic

compounds, tocopherols, ascorbic acid and carotenoids (Ho et al., 2020). Thus,

mushrooms can be used directly in the diet and promote health, taking advantage

of both the additive and synergistic effects of all bioactive compounds present

in it (Reis et al., 2011).

The cultivation of

edible mushrooms could become a way to augment farm income while making use of

crop-based residues. The growth of a variety of mushrooms requires different

type of substrates and availability of different type of materials. Substrates

such as logs, wood sawdust, rice straw and hull, banana leaves, maize stalk,

and various grasses can all support mushroom growth (Philippoussis, 2009). In

some parts of the Philippines, these substrates may not be available or are

available at relatively high prices. Thus, mushroom growers are continuously

searching for alternative substrates that may be more readily available or cost

effective, or that may provide higher yield and better mushroom quality (Royse

D et al., 2004).

With the need to

cultivate G. lucidum using lowcost inputs and locally available materials, this

project envisioned to determine the best culture media, grain and substrate in

terms of biological and cost efficiency. Discovering the best culture media,

grain and substrate for G. lucidum may lead to the development of mushroom

production technologies that may increase yield, and in effect further increase

farmers’ income.

Reference

Ho L, Zulkifli N, Tan

T. 2020. Edible mushroom: nutritional properties, potential nutraceutical

values, and its utilisation in food product development. An introduction

to mushroom 10

Reis F, Barros L,

Martins A, Ferreira I. 2011. Chemical composition and nutritional value of

the most widely appreciated cultivated mushrooms: an inter-species comparative

study. Food and Chemistry 128, 674-678

Philippoussis A. 2009.

Production of mushrooms using agro-industrial residues as substrates 10.1007/978-1-4020-9942-7_9

Royse D, Rhodes T, Ohga

S, Sanchez J. 2004. Yield, mushroom size and time to production of Pleurotus

cornucopiae (Oyster mushroom) grown on switch grass substrate spawned and

supplemented at various rates Bioresource Technology 91, 85-91

Yang F, Liau C. 1998.

Effect of cultivating conditions on the mycelial growth of Ganoderma

lucidum in submerged flask cultures Bioprocess Engineering 19, 233-236

Wagner R, Mitchell D,

Sassaki G, Amazonas M, Berovic M. 2003. Current techniques for the

cultivation of Ganoderma lucidum for the production of biomass,

ganoderic acid and polysaccharides Food Technol Biotechnol 41, 371-382

Azizi M, Tavana M,

Farsi M, Oroojalian F. 2012. Yield performance of lingzhi or reishi medicinal

mushroom, Ganoderma lucidum (W.Curt.:Fr.) P. Karst. (Higher

Basidiomycetes), using different waste materials as substrates International

Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms 14, 521-527

Wachtel-Galor S, Yuen

J, Buswell J, Benzie I. 2011. Herbal medicine: Biomolecular and clinical

aspects, 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press

Chang S, Buswell J. 2008.

Safety, quality control and regulational aspects relating to mushroom

nutriceuticals Proceedings of 6th International Conference in Mushroom Biology

and Mushroom Products. GAMU Gmbh, Krefeld, Germany

Boh B, Berovic M, Zhang

J, Zhi-Bin L. 2007. Ganoderma lucidum and its pharmaceutically

active compounds Biotechnol Ann. Rev 13, 265-301

Tiwari C, Meshram P,

Patra A. 2004. Artificial cultivation of Ganoderma lucidum Indian

Forester 130, 1057-1059

Royse D, Bahler B,

Bahler C. 1990. Enhanced yield of shiitake by saccharide amendment of the

synthetic substrate Appl. Environ. Microbiology 56(2), 479

Chang S, Lau O, Cho K. 1981.

The cultivation and nutritive value of Pleurotus sajor-caju European

J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 12, 58-62

Reyes R, Grassel W, Rau

R. 2009. Coconut water as a novel culture medium for the biotechnological

production of schizophyllan. J. Nature Stud 7, 43-48

De Leon A, Guinto L, De

Ramos P, Kalaw S. 2017. Enriched cultivation of Lentinus squarrosulus (Mont.)

Singer: A newly domesticated wild edible mushroom in the Philippines

Mycosphere 8(3), 615-629

Landingin H, Francisco

B, Dulay R, Kalaw S, Reyes R. 2020. Optimization of culture conditions for

mycelial growth and basidiocarp production of Cyclocybe cylindracea (Maire). CLSU

International Journal of Science & Technology 4(1), 1-17

Dulay R, Garcia

E. 2017. Optimization and enriched cultivation of Philippine (CLSU) strain

of Lentinus strigosus (BIL1324). Biocatalysis and Agricultural

Biotechnology 12, 323-328

Borlingame B, Mouille

B, Charrondiere R. 2009. Nutrients, bioactive non-nutrients, and

antinutrients in potatoes Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 22, 494-502

Kalaw S, Alfonso D,

Dulay R, De Leon A, Undan JQ, Undan JR, Reyes R. 2016. Optimization of

culture conditions for secondary mycelial growth of wild edible mushrooms from

selected areas in Central Luzon, Philippines Current Research in Environmental

& Applied Mycology 6(4), 277-287

Magday J, Bungihan M,

Dulay R. 2017. Optimization of mycelial growth and cultivation of fruiting

body of Philippine wild strain of Ganoderma lucidum Current Research

in Environmental & Applied Mycology 4.

Awi-Waadu G, Stanley O. 2010.

Effect of substrates of spawn production on mycelial growth of oyster mushroom

species Research Journal of Applied Sciences 5(3), 161-164

Tinoco R, Pick M,

Duhalt R. 2001. Kinetic differences of purified laccases from six Pleurotus

ostreatus strains Lett. Applied Microbiol 32, 331-335

Dulay R, Kalaw S, Reyes

R, Cabrera E, Alfonso N. 2012. Optimization of cuture conditions for

mycelial growth and basidioscarp production of Lentinus tigrinus (Bull)

Fr., a new record of domesticated wild edible mushroom in the Philippines

Philipp Agric Scientist 95, 209-214

Gurung O, Budathoki U,

Parajuli G. 2012. Effect of different substrates on the production

of Ganoderma lucidum (Curt.: Fr.) Karst. Our nature 10(1), 191-198

Adesina F, Fasidi I,

Adenipekun C. 2011. Cultivation and fruit body production of Lentinus

squarrosulus Mont. (Singer) on bark and leaves of fruit trees supplemented

with agricultural waste. African Journal of Biotechnology 10(22), 4608-4611

Moonmoon M, Shelly N,

Khan A, Valdin N. 2011. Effects of different levels of wheat bran, rice

bran and maize powder supplementation with sawdust on the production of

shiitake mushroom [Lentinula edodes (Bark) Singer] Saudi Journal of

Biological Sciences 18, 323-328.

Source : Development of low-cost cultivation protocol for Ganoderma lucidum (Curtis) P. Karst

%20in%20full.JPG)

0 comments:

Post a Comment