JK. Talukdar, and

AK. Haloi from the different institute of the india, wrote a research

article about Indian Flying Fox in Goalpara, Assam: Roost Ecology &

Behavior, entitled, "Roost ecology, population size, behavioral patterns

and morphometric analysis of Indian flying fox (Pteropus medius; Temminck,

1825) in the Goalpara District of Assam, India". This research paper

published by the International Journal of Biosciences | IJB. an

open access scholarly research journal on Biosciences. under

the affiliation of the International Network For Natural Sciences |

INNSpub. an open access multidisciplinary research journal publisher.

Abstract

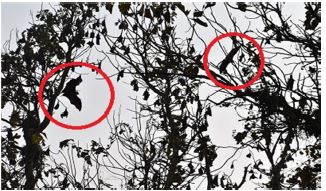

The present study was conducted at Krishnai Forest Range Office Campus (26°2′ 0″ North, 90°40′ 0″ East) situated at Goalpara district of Assam. Throughout the pre-monsoon season (March–May 2022), the survey location was periodically visited. The current study aims to identify the numerous roosting trees used by Indian flying foxes (P. medius), their diurnal behavioral pattern, and to assess the population size of the species together with their morphometric variations. A large mean colony size (5479 332.99) of P. medius bats was found in the study site, residing in a number of preferred roosting trees (n = 101). In April 2022, a population count of 5509 bats was recorded as the mean population size. However, the population count varies in March (5871) and May (5057). Population fluctuation was mainly due to inter-colony migration and other environmental factors. A very high population density of 4094.91 was recorded. Direct roost count method was used to estimate the population size following standard literature key (Bates and Harrison, 1997). Different times of the day were used to record the diurnal roosting habit patterns of the bats. The most frequent behavior was sleeping, which was followed by grooming, wing flapping, and wing spreading. Two of the few captured bats (n) were used to analyze the morphometric variances. The average body weight of the specimens that were caught was 699 ± 26.87g, and the average forearm length was 172.05 ± 2.616g. When compared to the caught (P. medius) bat species, the mean value of the morphometric measurements revealed a substantial variation. Roosting site selection depends on their abundance, risk of predation, availability and distribution of food resources and physical environment. An essential species for maintaining the ecosystem’s equilibrium is the Indian flying fox. For the reforestation of the forest environment, it is regarded as a crucial method of seed dissemination and pollination. The study site was selected based on the very fact that earlier no prior study was carried out in this roosting site and proved to be a significant area sustaining bats for more than 30 years with approximately 80-85 % of the species (P. medius) roosts as year round.

Read more: Fungal Isolates: Inhibitory Indices Against Mycotoxins | InformativeBD

Introduction

Bats are the unique

group of sustained-flight mammals like birds belonging to the order Chiroptera

(Adhikari et al., 2010). Chiroptera (bats) account for one-fifth of mammalian

species and are the second largest among 26 mammalian orders (Suga, 2009;

Srinivasulu et al., 2010). Traditionally, the order Chiroptera is divided into

two distinct suborders Megachiroptera are Old World flying foxes distributed

within a family of 01 and the Microchiroptera includes laryngeal echolocating

bats and are distributed around 18 families (Mickleburgh et al., 1992; Koopman,

1993; Hutson et al., 2001, Simmons, 2005; Srinivasulu et al., 2010, Saikia,

2019). However, using molecular and phylogenetic methods, scientists have

proposed a new subdivision of Chiroptera, namely Yinpterochiroptera, which

includes the megabat family Pteropodidae along with the Microbat families

Rhinolophidae, Rhinopomatidae, and Megadermatidae, and Yangochiroptera

including the remaining Microbat families (Teeling et al., 2002). Bats are

distributed worldwide and are more ecologically diverse than any other group of

mammals (Handley et al., 1996). They are widespread and have been recorded

worldwide, with the exception of Antarctica and some oceanic islands

(Mickleburgh et al., 2002). More than 1,400 bat species are known worldwide,

190 species belong to the suborder Megachiroptera, which is distributed within

a single family Pteropodidae (Bat Conservation International 2021; Talmale et

al., 2018).

There are 14 species of

Pteropodidae in India and members of this family are colloquially known as

flying foxes (Saikia et al., 2018). The Indian fruit bat (Pteropus medius) is a

species of fruit bat in the Pteropodidae family. The Indian flying fox is known

locally as Pholkhowa Borbaduli (Frugivorous; large bat) in Assamese. Pteropus

medius is a social species living in a large daytime roost and is one of the

largest flying fox species of the subcontinent stretching from Bangladesh,

China, India, Nepal, Pakistan to Sri Lanka (Khatun, 2014). Most fruit bats

studied are moderately or strongly colonial (Rainey et al., 1992). Perhaps some

of them form colonies comprising a few hundred to millions of individuals

(Nowak, 1999).

Their good sense of smell and sight locate sources of ripe fruit. Flowering plants are a good and preferred food source and all fruit bat species feed only on nectar, flowers, pollen and fruit, which explains their limited tropical distribution. It is considered to be an essential means of seed dispersal and pollination for reforestation of the forest ecosystem (Ali, 2010).

Indian flying fox is one of the beneficial members of the animal community that acts as a key species to keep the ecosystem in balance. Despite their high utilitarian role, these bats are mistreated in India and are highly vulnerable to environmental nuisance. Many resting populations of the species have declined sharply in response to anthropogenic activity.

They are increasingly threatened locally by the hunt for meat and medicine, the felling of roosting trees for road construction and other development purposes have hit the Indian fruit bat population acutely (Bhandarkar et al., 2018). There is no official protection for Indian fruit bats or the other two species of fruit bats in India and indeed the Government of India's Wildlife Protection Act 1972 included them all in the schedule IV- Vermin (ENVIS, 2022). The species requires appropriate conservation measures to protect and continue its ecological role in restoring forests.

Although Northeast India has a rich diversity of bats, this mammalian species has been studied very little in the region. The north-eastern region of India has an exceptional wealth of mammals, including over 70 bat species, some of which have only recently been described or reported (Bates & Harrison 1997; Thong et al., 2018). In Assam, there is very little published material on the Indian flying fox or the bat community as a whole (Sharma et al., 2020).

A monograph by Bates & Harrison (1997) listed 28 bat species from Assam. The state's bat diversity is apparently not very high, comprising about 30 recorded species (Ali, 2022). A very limited information regarding the status of bat diversity in the state has found it mentioned in (Bates & Harrison 1997; Sinha, 1999; Ali et al., 2010; Boro et al., 2013; Boro & Saikia, 2015; Rahman et al., 2017; Sharma et al., 2020, Saikia et al., 2022; Ali, 2022). Considering the lack of comprehensive surveys and field studies documenting the diversity, distribution and status of the state's bat fauna, the reported species richness in the region would undoubtedly be an underestimate (Saikia et al., 2018). This study was an initial effort in the area, a newly located roosting site, with the goal of identifying the various roosting trees used by Indian flying foxes (P. medius), their diurnal behavioural pattern, and to estimate the population size as well as their morphometric variations.

Reference

Ali A. 2010. Population trend and conservation status of Indian flying fox (Pteropus giganteus) Brunnich, 1782 (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) in western Assam. The Ecoscan 4(4), 311-312.

Ali A. 2022.

Species diversity of bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) in Assam, Northeast India.

Journal of Wildlife and Biodiversity 6(3), 115-125.

Animalia. 2023.

Accessed on 16th May 2023. https://Indian Flying Fox – Facts, Diet,

Habitat & Pictures on Animalia.bio

Bat Conservation

International (BCI). 2022. An Unlikely Hero with Global Impact, Available

online: Accessed on 25 March 2022. https://www.batcon.

org/about-bats/bats-101/

Bates PJJ, Harrison

DL. 1997. Bats of the Indian Subcontinent, Harrison Zoological Museum

Publications, Sevenoaks, UK 1- 258.

Bennet M. 1993.

Structural modifications involved in the fore and hind limb grip of some flying

foxes, Chiroptera: Pteropodidae, J. Zool. London 229, 237-248.

Bhandarkar SV, Paliwal

GT. 2018. Ecological notes on roosts of Pteropus Giganteus (Brunnich,

1782) in eastern Vidarbha, Maharashtra. International Journal for Environmental

Rehabilitation and Conservation, ISSN: 0975 – 6272.

Boro A, Saikia PK,

Saikia U. 2018. New records of bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) from Assam,

northeastern India with a distribution list of the bat fauna of the state,

Journal of Threatened Taxa 10(5), 11606-11612. DOI:

10.11609/jot.3871.10.5.11606-11612

Brigham RM, Aldridge

HDJN, Mackey RL. 1992. Variation in habitat use and prey selection by yuma

bats, Myotis yumanensis . Journal of Mammalogy 73, 640-645.

Census of India. 2011.

District Census Handbook Goalpara, Village and Town Directory, Assam. Series-19,

Part XII-A, 63-403.Climate Goalpara (India). 2022. Available online:

https://en.climatedata24654/.

Fenton MB, Robert

MRB. 1980. Mammalian Species. American Society of Mammalogists. No. 142,

Myotis lucifugus pp. 1-8 (8 pages). https://doi.org/10.

2307 /3503792

Global Biodiversity

Information Facility. 2021. Gbif (Online).https://www.gbif.org. Accessed

18 Feb. 2021

Gulshan A. 2021.

Why our city’s bats are most misunderstood. The Hindu (Online). https://www. thehindu.com. Accessed 02 May .2021

Handley D, Elisabeth

KVK, Handley OC. 1996. Long-Term Studies of Vertebrate Communities 1996.,

chptr 16: Organization, Diversity, and Long-Term Dynamics of a Neotropical Bat

Community. Pages 503-553.

Herd RM, Fenton

MB. 1983. An electrophoretic, morphological, and ecological investigation

of a putative hybrid zone between Myotis lucifugus and Myotis

yumanensis (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae), Canadian Journal of

Zoology 61(9), 2029-2050

Hill JE, Smith

JD. 1984. Bats: A Natural History, British Museum (Natural History),

London.

Hutson AM, Mickleburgh

SP, Racey PA. 2001. Microchiropteran Bats. Global Status Survey and

Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC Chiroptera Specialist, Group. IUCN, Gland,

Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK.

Jeyapraba L. 2016.

Roosting Ecology of PteropusGiganteus (Brunnich , 1782) Indian Flying Fox And

Threats For Their Survival, IJCRD 1, ISSN (Online), 2456 – 3137pp.

Kate B. 1999.

Expedition field techniques: Bats 1999, ISBN 978-0-907649-82-3.Royal

Geographical Society with IBG, 1 Kensington Gore London, SW7 2AR.

Khatun M, Ali A, Sarma

S. 2014. Population fluctuation at Indian Flying Fox (Pteropus giganteus)

colonies in the Kacharighat Roosting Site of Dhubri district of Assam, Int. J.

Pure App. Biosci 2(4), 184-188.

Koopman KF. 1993.

Order Chiroptera. In Mammal Species of the World (eds D.E. Wilson & D.M.

Reeder), pp. 137-232, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC.

Krystufek B. 2009.

On the Indian flying fox (Pteropusgiganteus) colony in Peradeniya Botanical

Gardens, Srilanka” .Hystrix It. Journal of Mammalogy 20(1), 29-35.

Kunz TH. 1982.

Roosting ecology. In: Ecology of bats (Kunz., TH. ed). Plenum publishing. New

York. pp 1-55.

Kunz TH. 1988.

Ecological and behavioral methods for the study of bats. 1st ed. Smithsonian

Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Mickleburgh SP, Hutson

MA, Racey PA. 2002. A review of the global conservation status of bats.

Oryx 36(1), 18-34

Nowak RM. 1999.

Walker’s mammals of the world. 6th edition, The Johns Hopins University Press,

Baltimore, Maryland 1(1), 836.

Rahman A, Choudhury

P. 2017. Status and population trend of chiropterans in Southern Assam,

India. Biodiversity International Journal 1(4), 121-132. DOI:

10.15406/bij.2017.01.00018.

Rainey WE, Pierson

ED. 1992. Distribution of Pacific Island flying foxes. In: Proceedings of

an International Conservation Conference, D.E. Wilson and G.L. Graham, (Eds).

U.S. Fish and Wildl. Serv. Biol. Rept, pp 111-121.

Saha A, Hasan KM,

Feeroz MM. 2015. Diversity and Morphometry of Chiropteran Fauna in

Jahangirnagar University Campus, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 43(2).

Saikia U. 2018. A

review of Chiropterological studies and a distributional list of the Bat Fauna

of India 118(3), DOI: 10.26515/rzsi/v118/i3/2018/121056

Saikia U. 2019.

Demystifying bats from enigma to science, MOEF, ZSI, Shillong 1-13pp.

Sharma P, Rai M. 2020.

Population Status of Indian Flying Fox, Pteropus giganteus in Urban Guwahati,

Assam, India: A Case Study, Applied Ecology and Environmental Sciences 8(5), 287-293.

DOI: 10.12691/aees-8-5-16.

Simmons NB. 2005.

Order Chiroptera. In: Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic

Reference”, D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder, eds., Smithsonian Institution Press,

Washington, DC.

Sinha YP. 1980.

The bats of Rajasthan : Taxonomy and zoogeography. Rec. zool. Surv. India 76, 7-63.

Sinha YP. 1999.

Contribution to the knowledge of Bats (Mammalia : Chiroptera) of North Eastm

Hills, India. Rec. zool. Surv. India, Occ. Paper No. 174, 1-52.

Springer MS, Teeling

EC, Madsen O, Stanhope MJ, de Jong WW. 2001. Integrated fossil and

molecular data reconstruct bat echolocation. Proceedings of the National

Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 98, 6241-6246.

Srinivasulu C, Racey

AP, Mistry S. 2010. A key to the bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) of South

Asia. Journal of Threatened Taxa, ISSN 0974-7907 (online).

Suga N. 2009. In

Encyclopedia of Neuroscience, Elsevier Ltd. ISBN, 978-0-08-045046-9.

Talmale SS, Saikia

U. 2018. Fauna of India Checklist: A Checklist of Indian Bat Species

(Mammalia: Chiroptera), Zoological Survey of India, Version 2.0. Online

publication, 1-17 pp.

Teeling E, Madsen O,

Bussche RVD, Jong W, Stanhope M, Springer M. 2002. Microbat monophyly and

the convergent evolution of a key innovation in old world rhinolophoid

microbats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States

of America 99, 1431-1436.

The Animal Diversity

Web. 2021. The Animal Diversity Web (online). https://animaldiversity.org.

Accessed 24 May. 2022.

Thomas WD. 1988.

The Distribution of Bats in Different Ages of Douglas-Fir Forests. The Journal

of Wildlife Management 52(4), 619-626.

Thong VD, Mao XG,

Csorba P, Ruedi M, Viet NV, Loi DN, Nha PV, Chachula O, Tuan TA, Son TN, Fukui

D, Saikia U. 2018. First records of Myotisaltarium (Chiroptera:

Vespertilionidae) from India and Vietnam. Mammal Study 43, 67-73pp.

Wilson DE, Reeder

DM. 2005. Mammal Species of the World: a taxonomic and geographic

reference, 3rd ed: 1-2142.

%20in%20full.JPG)

0 comments:

Post a Comment