Hyacinthe Kanté-Traoré, Marie Dufrechou , Dominique Le Meurlay , Vanessa Lançon-Verdier , Hagrétou Sawadogo-Lingani , and Mamoudou H. Dicko from the different institute of the Burkina Faso and France wrote a research article about, Mango Varieties of Burkina Faso: Properties & Potential Uses entitled,"Physicochemical properties and potential use of six mango varieties from Burkina Faso" this research paper published by the International Journal of Biosciences| IJB an open access scholarly research journal on Biology, under the affiliation of the International Network For Natural Sciences | INNSpub, an open access multidisciplinary research journal publisher.

Abstract:

The quality profile of

the six most important mango varieties from Burkina Faso, as well as their

potential use, was investigated. It appeared that Amélie variety

showed the highest levels of total sugars (74.49±0.04 % dry weight), β-carotene

(1752.72±41.64 µg/100 g of fresh weight), vitamin C (58.94±1.77 mg/100 g of

fresh weight), titratable acidity (1.56±0.01 %), and energy value (80.55±0.01

Kcal/100 g dry weight). However, this variety has the lowest soluble

solids/titratable acidity ratio (TSS/TA) of 11.24±0.17 and the lowest total

fiber content (1.87±0.03 % fresh weight). Kent variety contained the

highest levels of pulp (81.31±1.67 % fresh weight), total soluble solids

(23.1±0.00 % fresh weight), total fiber content (2.77±0.08 % fresh weight) and

the lowest β-carotene content (220.21±14.97 µg/100 g fresh weight). All

varieties have significant levels of total phenolic compounds (mini-maxi

content). This study not only showed significant differences in biochemical

contents and physical characteristics among mango varieties but will also guide

mango processors and nutritionists in choosing the most suitable varieties

according to target food products.

Read more: Fighting ChestnutBlight: Antagonistic Microscopic Fungi | InformativeBD

Introduction

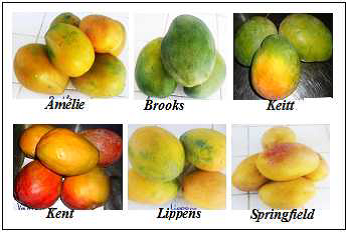

Mango (Mangifera indica L.) fruit is among the main speculation of the fruit sector in most tropical countries worldwide. In Burkina Faso, its cultivation covers 58 % of the orchards and its production is estimated to be 56 % of the annual all fruits production (APROMAB, 2016). The annual production of mango has increased from 337 101 tons in 2008 to 404 400 tons in 2014 (Ouédraogo et al.,2017) with an operating area of 33,700 hectares. About forty varieties of mango are available in Burkina Faso. Among these, varieties of mango trees identified in the orchards in the largest production area (Comoé, Kénédougou and Houet provinces located in western Burkina Faso) are Brooks (29.61%), Lippens (25.15 %), Amélie (18.96 %), Kent (18.65%), Keitt (5.52 %) and Springfield (2.07 %) (Guira,2008). The distribution of mango varieties in orchards has been studied by Rey et al. (2004). This distribution varied according to the area. For instance, in the province of Houet, the Amélie variety represents a high proportion of the mangoes produced compared to the colored varieties (Kent, Keitt). Amélie variety occupied 40 to 50 % of the cultivated land (PAFASP, 2011). The production yield is around 150 to 200 kg of fruit/tree for Brooks and Lippens varieties, 100 to 150 kg of fruit/tree for Amélie, Keitt and Kent varieties and 50 to 100 kg of fruit/tree for Springfield variety (Guira, 2008). In addition to the high agricultural potential of mango, the pulp of this fruit has a high nutritional value. Indeed, it is an excellent source of β-carotene (provitamin A), vitamin C, carbohydrates, fibers, phenolic compounds and minerals (Robles-Sanchez et al.,2009; Ma et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2013; Somé et al.,2014). Levels of these compounds are significantly different among varieties and are dependent on agronomic, climatic and environmental conditions. Furthermore, mangos being a climacteric fruit, the degree of maturity, growing conditions and storage conditions highly influence the levels of these metabolites. Secondary metabolites are powerful antioxidants that reduce oxidative stress and have anti-cancer properties ((Kim et al., 2003; Chiou et al.,2007). For instance, carotenoids play an important role in human health by acting as a source of provitamin A or as protective anti-oxidants necessary for good reproduction and growth, in the normal operation of the eye system, and in the integrity of epithelial cells and the functionality of the immune system (Murkovic et al., 2002).

Studies on mango varieties from Burkina Faso

with respect to diseases and pest attacks have been previously performed

(Vayssieres et al., 2008;Ouédraogo, 2011). Moreover, Amélie fruit variety

has been studied on aspects related to technological valorization, chemical

composition and nutritional value and on the storage effects on vitamin

C, carotenoids and browning (Sawadogo-Lingani and Traoré, 2001, 2002a;

Sawadogo-Lingani et al., 2002;Sawadogo-Lingani et al, 2005). Other studies

dealt with methods of producing unconventional food for pigs based on mango

wastes in Burkina Faso(Kiendrebeogo et al., 2013). The drying technology ofthe

Brooks variety has been studied and the physicochemical, biochemical, and

technological characterization of the different existing mango varieties were

determined (Rivier et al., 2009). Yet, without the knowledge and mastery of

these characteristics, qualitative and standardized processing cannot be

achieved. Production of puree ,concentrates and beverages from mango

require specific characteristics, where the ratio of total sugar content/acid

(TSS/TA) associated with an intense yellow-orange color and soft texture play

major roles. On the other hand, the production of dried mangoes, frozen or canned

fruit pieces requires firmer fruits for which color is important. The present

work aims to determine the biochemical characteristics of the six most exported

and most processed mango varieties in Burkina Faso. The characterization of

these six varieties will allow proposing of appropriate use technologies for each

variety.

Reference

Arias R, Lee TC,

Logendra L, Janes H. 2000. Correlation of lycopene measured by HPLC with

the L*, a*, b* color readings of a hydroponic tomato and the relationship of

maturity with color and lycopene content. Journal of Agricultural and Food

Chemistry 48, 1697–1702.

Association

Interprofessionnelle Mangue Du Burkina (APROMAB). 2016. Rapport de

l’atelier bilan de la campagne mangue 2016 de la commercialisation de la

mangue. Bobo-Dioulasso, novembre 2016. 28 p.

Bafodé BS. 1988.

Projet de transformation et de conditionnement des mangues à Boundiali en Côte

d’Ivoire. SIARC (Section des ingénieurs alimentaires/région chaude Montpellier

87 p.

Champ M, Langkilde AM,

Brouns F, Kettlitz B, Le Bail Collet Y. 2003. Advances in dietary fibre

characterisation. 1. Definition of dietary fibre, physiological relevance,

health benefits and analytical aspects. Nutrition Research Reviews 16, 71–82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1079/NRR200254

Chiou A, Karathanos VT,

Mylona A, Salta FN, Preventi F, Andrikopoulos NK. 2007. Currants (Vitis

vinifera L.) content of simple phenolics and antioxidant activity. Food

Chemistry 102, 516-522.

Cocozza FM, Jorge JT,

Alves RE, Filgueiras HAC, Garruti DS, Pereira MEC. 2004. Sensory and

physical evaluations of cold stored ‘Tommy Atkins’ mangoes influenced by 1-MCP

and modified atmosphere packaging. Acta Horticulture 645, 655–661.

D’Souza MC, Singha S,

Ingle M. 1992. Lycopene concentration of tomato fruit can be estimated

from chromaticity values. Hort Science 27, 465–466.

Dubois M, Gilles KA,

Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. 1956. Colorimetric method for

determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical Chemistry 28, 350–356.

Elsheshetawy HE, Mossad

A, Elhelew WK, Farina V. 2016. Comparative study on the quality

characteristics of some Egyptian mango varieties used for food processing.

Annals of Agricultural Science 61(1), 49–56.

Frenich AG; Torres MH,

Vega AB, Vidal JM, Bolanos, PP. 2005. Determination of ascorbic acid and carotenoids

in food commodities by liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry detection.

Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 53, 7371-7376.

Gonzalez-Aguilar GA,

Buta JG, Wang CY. 2001. Methyl jasmonate reduces chilling injury symptoms

and enhances color development of ‘Kent’ mangoes. Journal of Agricultural 81, 1244–1249.

Grundy

MML, Edwards CH, Mackie AR, Gidley MJ, Butterworth PJ, and Ellis

PR. 2016. Re-evaluation of the mechanisms of dietary fiber and

implications for macronutrient bioaccessibility, digestion and postprandial

metabolism. British Journal of Nutrition 116(5), 816-33.

Guira M. 2008.

Description des principales variétés de manguiers cultivées au Burkina Faso.

Fiche technique N°2.

Hernández Y, Lobo MG,

González M. 2006. Determination of vitamin C in tropical fruits: A

comparative evaluation of methods. Food Chemistry 96, 654-664.

Hirschler R. 2012.

Whiteness, Yellowness and Browning in Food Colorimetric In: Color in Food.

Technological and Psychophysical Aspects. Edited by José Luis Caivano and María

Del Pilar Buera. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL: 2012.

Hu W, Jiang Y. 2007.

Quality attributes and control of fresh-cut produce. Stewart Postharvest

Rev, 3, 1-9.

Ibarra-Garza IP,

Ramos-Parra PA, Hernández-Brenes C, Jacobo-Velázquez DA. 2015. Effects of

postharvest ripening on the nutraceutical and physicochemical properties of

mango (Mangifera indica L. cv Keitt) Postharvest Biology and

Technology 103, 45–54.

Jha SN, Chopra S,

Kingsly ARP. 2007. Modeling of color values for non-destructive evaluation

of maturity of mango. Journal of Food Engineering 78, 22–26.

Kim D, Jeong SW, Lee

CY. 2003. Antioxidant capacity of phenolic phyto-chemicals from various

cultivars of plums. Food Chemistry 81, 321-326.

Kiendrebeogo T, Mopate

Logtene Y, IDO G, kabore-Zoungrana CY. 2013. Procédés de production

d’aliments non conventionnels pour porcs à base de déchets de mangues et

détermination de leurs valeurs alimentaires au Burkina Faso. Journal of Applied

Biosciences 67, 5261–5270 ISSN 1997–5902.

Kothalawala SG,

Jayasinghe JMJK. 2017. Nutritional Evaluation of Different Mango Varieties

available in Sri Lanka. International Journal of Advanced Engineering Research

and Science (IJAERS), 4(7), ISSN: 2349-6495(P)/2456-1908(O). https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijaers.4.7.20

Liu FX, Fu SF, Bi XF,

Chen F, Liao XJ, Hu XS, Wu JH. 2013. Physicochemical and anti-oxidant

properties of four mango (Mangifera indica L.) varieties in China. Food

Chemistry 138, 396–405.

Ma X, Wu H, Liu L, Yao

Q, Wang S, Zhan R, Xing S, Zhou Y. 2011. Polyphenolic compounds and

anti-oxidant properties in mango fruits. Scientia Horticulturae, 129, 102–107.

Mahayothee B, Muhlbaue

W, Neidhart S, Carle R. 2004. Influence of postharvest ripening process on

appropriate maturity drying mangoes ‘Nam Dokmai’ and ‘Kaew’. Acta

Horticulture 645, 241–248.

Malundo TMM,

Shewfelt RL, Ware GO, Baldwin EA. 2001. Sugars and Acids Influence Flavor

Properties of Mango (Mangifera indica). Journal of the American Society for

Horticultural Science 126(1), 115–121.

Medlicott AP, Thompson

AK. 1985. Analysis of Sugars and Organic Acids in Ripening Mango

Fruits (Mangifera indica L. var Keitt) By High Performance Liquid

Chromatography Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 36, 561-566.

Murkovic M, Mulleder U,

Neunteufl H. 2002. Carotenoid Content in Different Varieties of Pumpkins.

Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 15, 633–638. https://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jfca.2002.1052. http://www.idealibrary.com

Ornelas-Paza JDJ,

Yahiab EM. 2014. Effect of the moisture content of forced hot air on the

postharvest quality and bioactive compounds of mango fruit (Mangifera indica L.

cv. Manila). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 94, 1078–1083.

Ouédraogo N, Boundaogo

M, Drabo A, Savadogo R, Ouattara M, Dioma EC, Ouédraogo M. 2017. Guide de

la transformation de la mangue par le séchage au Burkina Faso. UNMO/CIR, SNV,

PAFASP, décembre 2017. 56 p.

Ouédraogo SN. 2011.

Dynamique spatio temporelle des mouches des fruits (diptera, tephritidae) en

fonction des facteurs biotiques et abiotiques dans les vergers de manguiers de

l’Ouest du Burkina Faso. Thèse de doctorat spécialité écophysiologie.

Université Paris Est, Ecole doctorale science de la vie et de la santé, 184 p.

Padda MS, Amarante CVT,

Garciac RM, Slaughter DC, Mitchama EJ. 2011. Methods to analyze

physicochemical changes during mango ripening: A multivariate approach.

Postharvest Biology and Technology 62, 267-274.

Passannet AS,

Aghofack-Nguemezi J, Gatsing D. 2018. Variabilité des caractéristiques

physiques des mangues cultivées au Tchad: caractérisation de la diversité

fonctionnelle. Journal of Applied Biosciences 128, 12932 -12942. ISSN

1997-5902. https://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jab.v128i1.6

Programme d’Appui aux

Filières Agro-Sylvo-Pastorales (PAFASP). 2011. Analyse des chaines de

valeur ajoutée des filières Agro-Sylvo-Pastorales: bétail/viande, volaille,

oignon et mangue. CAPES, rapport définitif, 212 p.

Renard CMGC. 2005b.

Variability in cell wall preparations: Quantification and comparison of common

methods. Carbohydrate Polymers 60, 515–522.

Rivier M, Méot JM,

Ferré T, Briard M. 2009. Le séchage des mangues Éditions Quæ, CTA, e-ISBN

(Quæ) : 978-2-7592-0342-0 ISBN (CTA): 978-92-9081-421-4.

Robles-Sánchez RM,

Rojas-Graüb MA, Odriozola-Serrano I, González-Aguilara GA, Martín-Belloso O. 2009.

Effect of minimal processing on bioactive compounds and anti-oxidant activity

of fresh-cut ‘Kent’ mango (Mangifera indica L.). Postharvest Biology and

Technology 51, 384–390.

Sajib MAM, Jahan S,

Islam MZ, Khan TA, Saha BK. 2014. Nutritional evaluation and heavy metals

content of selected tropical fruits in Bangladesh. International Food Research

Journal 21(2), 609-615.

Sawadogo-Lingani H,

Traoré SA. 2001. Critères d´appréciation de la maturité physiologique de

la variété de mangue Amélie du Burkina Faso. Sciences et Techniques, série

Sciences Naturelles et Agronomie 25(1), 60-71.

Sawadogo-Lingani H,

Traoré SA. 2002a. Composition chimique et valeur nutritive de la mangue

Amélie (Mangifera indica L.) du Burkina Faso.2002. Journal des Sciences 2(1), 35-39.

Sawadogo-Lingani H,

Thiombiano G, Traoré SA. 2002. Effets des prétraitements et du séchage

solaire sur la vitamine C, les caroténoïdes et le brunissement de la mangue.

Sciences et Techniques, série Sciences de la santé 25(2), 75-88.

Sawadogo-Lingani H,

Thiombiano G, Traoré SA. 2005. Effets du stockage sur la vitamine C, les

caroténoïdes et le brunissement de la mangue Amélie séchée. Revue CAMES, Série

A, Sciences et Médecine, 3, 62-67.

Singleton VL, Orthofer

R, Lamuela-Raventos RM. 1999. Analysis of total phenols and other

oxidation substrates and anti-oxidants by means of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent.

Methods Enzymol. 299, 152–178.

Somé TI, Sakira AK,

Tamimi ED. 2014. Determination of β-carotene by High Performance Liquid

Chromatography in Six Varieties of Mango (Mangifera indica L) from Western

Region of Burkina Faso American Journal of Food and Nutrition 2(6), 95-99.

Vayssieres JF, Korie S,

Coulibaly T, Temple L, Boueyi S. 2008.The mango tree in northern

Benin (1), variety inventory, yield assessment, early infested stages

of mangos and economic loss due to the fruit fly (Diptera Tephritidae). Fruits, 63, 1-22.

Vasquez-Caicedo AL,

Neidhart S, Carle R. 2004. Postharvest ripening behavior of nine Thai

mango varieties and their suitability for industrial applications. Acta

Hortic. 645, 617–625.

Veda S, Platel K,

Srinivasan K. 2007. Varietal Differences in the Bioaccessibility of

β-Carotene from Mango (Mangifera indica) and Papaya (Carica papaya) Fruits.

Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55, 7931–7935.

West C, Castenmiller

JJM. 1998. Quantification of the ‘SLAMENGHI’ factors for carotenoid

bioavailability and bioconversion. International Journal for Vitamin and

Nutrition Research 68, 371–377.

Wongmetha O, Ke LS,

Liang YS. 2015. The changes in physical, bio-chemical, physiological

characteristics and enzyme activities of mango cv. Jinhwang during fruit growth

and development. NJAS – Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences 72–73, 7–12.

%20in%20full.JPG)

0 comments:

Post a Comment